Life and Death on a Scorched Planet: What I Learned From “The Heat Will Kill You First”

I remember the exact moment I was radicalized about climate change.

Standing on the front porch of our new home in Southern California in the summer of 2020, I watched the sky turn a burnt orange as wildfires blazed in the inland summer heat. The particles of smoke didn’t just fill the air—they filled our lungs. I coughed and wheezed throughout the day and night, unable to think or work effectively, as my body’s systems were overwhelmed by an atmosphere suddenly hostile to human life.

Far more worryingly, my wife Lauren was pregnant with our first child at the time. Every parenting book I’d read emphasized the importance of clean air for fetal development, and here we were, trapped in a toxic cloud. We sealed the windows and doors on the worst days, bought half a dozen air purifiers, and cranked the AC as high as it would go. But still, I laid awake at night, feeling powerless against a force far beyond my control.

It was that summer when climate change stopped being an abstract concept and became viscerally personal for me. I realized that this wasn’t a one-time freak event—every summer we could expect deteriorating air quality from rampant wildfires. It had become part of the backdrop of our lives in Southern California, as predictable as June gloom and earthquake tremors.

Picture how this scenario is likely to play out over the next twenty years: You’re trying to work from home on a sweltering afternoon when the power flickers. Your computer monitor goes dark. The air conditioning sputters to a stop. Within minutes, the room temperature climbs from a comfortable 72 degrees to an oppressive 85, then 90. Your body starts producing sweat faster than it can evaporate. Your thinking becomes sluggish. The careful systems you’ve built—both digital and physical—begin to break down.

This convergence of physical heat, failing infrastructure, and human vulnerability isn’t just a temporary inconvenience. It’s a preview of the fundamental challenge that Jeff Goodell explores in The Heat Will Kill You First, a book that forced me to confront an uncomfortable truth: all our routines for productive living and working are built on the assumption of a stable climate. It no longer makes sense for me to teach people how to build productive systems without taking into account the increasing instability of our wider environment.

So many climate debates still focus on abstract concepts like emissions targets and policy frameworks, or expend tremendous energy trying to forecast the exact degree of temperature rise decades in the future. But an increasing number of people are discovering what I learned that smoky summer of 2020—climate change is already here, already personal, and already reshaping our daily lives.

Goodell’s book zeroes in on perhaps the most immediate and universal manifestation of that change: the direct impact of heat on human bodies, communities, and ecosystems.

As someone who thinks constantly about how we capture, organize, and act on information, I found myself reading his work through a unique lens. The climate crisis isn’t just an environmental problem. It’s fundamentally an information processing challenge. We’re drowning in data about rising temperatures, yet struggling to translate that knowledge into meaningful action. It’s the ultimate test of whether we can build a “Second Brain” not just for ourselves, but for our entire civilization.

In this piece, I’ll share the insights from Goodell’s book that surprised me the most, challenged my assumptions about human adaptability, and revealed why heat—not hurricanes, floods, or wildfires—represents the most profound threat to how we live and work in the 21st century.

The Invisible Killer Among Us

Here’s the fact that permanently shifted my understanding of climate risks: Heat kills more people than all other natural disasters combined.

A study in The Lancet estimated that 489,000 people worldwide died from extreme heat in 2019. That’s more than hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and earthquakes put together. It’s also more than deaths from guns or illegal drugs. Between 260,000 and 600,000 people die each year just from inhaling smoke from wildfires—a secondary effect of heat-amplified fires.

Yet heat remains largely invisible in our collective consciousness. We name hurricanes. We measure earthquakes on the Richter scale. We have sophisticated early warning systems for tornadoes. But heat waves? They pass through our communities like silent predators, leaving behind a trail of death that often goes uncounted and unnoticed.

This invisibility isn’t just a measurement problem—it’s a fundamental flaw in how we process information about gradual versus acute threats. Our brains, evolved to respond to immediate dangers, struggle to recognize slow-moving catastrophes. It’s the same reason we procrastinate on long-term projects while responding instantly to urgent emails.

Since 1970, Earth’s temperature has spiked faster than in any comparable forty-year period in recorded history. The eight years between 2015 and 2022 were the hottest on record. In 2022 alone, 850 million people lived in regions that experienced all-time high temperatures.

But numbers alone don’t capture what this means for human bodies and systems.

Researchers project that by 2100, half of the world’s population will be exposed to a life-threatening combination of heat and humidity. In parts of the world, temperatures will rise so high that simply stepping outside for a few hours “will result in death even for the fittest of humans.”

This isn’t a distant future scenario. It’s a reality that’s already emerging in unexpected places.

In western Pakistan, where only the wealthy have air conditioning, it’s already too hot for human survival several weeks each year. Holy cities like Mecca and Jerusalem, where millions gather for religious pilgrimages, have become what Goodell calls “caldrons of sweat.”

The scale of it already defies comprehension. In the summer of 2022, nine hundred million people in China—63 percent of the nation’s population—endured a two-month extreme heat wave that killed crops and sparked wildfires. One weather historian declared: “There is nothing in world climatic history which is even minimally comparable to what is happening in China.”

The economic toll is also staggering. Researchers at Dartmouth College estimate that since the 1990s, extreme heat waves have cost the global economy $16 trillion. But the human costs go far beyond GDP:

- Heat lowers children’s test scores

- It raises the risk of miscarriage in pregnant women

- Prolonged exposure increases death rates from heart and kidney disease

- When stressed by heat, people become more impulsive and prone to conflict

- Racial slurs and hate speech spike on social media during heat waves

- Suicides rise

- Gun violence increases

- Sexual assaults become more frequent

In Africa and the Middle East, studies have found direct links between higher temperatures and the outbreak of civil wars.

Heat doesn’t just kill our bodies. It kills our civilized selves.

The Machine Inside: Understanding Our Thermal Limits

Humans are heat machines. Just being alive generates heat.

Every thought, every heartbeat, every breath produces thermal energy that must be dissipated. When you move a muscle, only about 20 percent of the energy goes to the actual contraction—the other 80 percent is released as heat.

This biological fact creates an absolute temperature ceiling for human survival: a wet bulb temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius). Beyond that threshold, our bodies generate heat faster than we can dissipate it, regardless of shade, fans, or how much water we drink.

Drinking water by itself doesn’t actually cool your core body temperature. While dehydration can exacerbate heat exhaustion, you can be fully hydrated and still die of heatstroke. The only effective treatment is rapid cooling of core body temperature, through ice baths, cooling the palms and soles where blood circulates close to the surface, or other direct cooling methods.

As a systems thinker, I’m fascinated by second and third-order effects—the cascading consequences that ripple out from initial changes, like the spreading ripples in a pond. Goodell’s exploration of how heat is redrawing the map of disease distribution revealed consequences I hadn’t imagined.

For example, we know that the heat-loving Aedes aegypti mosquito is expanding its range northward and to higher altitudes. By 2080, five billion people—60 percent of the world’s population—may be at risk of dengue fever.

Mexico City, historically too cold for these mosquitoes, has always remained mostly free of yellow fever, dengue, and Zika. But as temperatures rise, Aedes aegypti is moving in, bringing these diseases to 21 million unprepared residents. I’ve personally noticed the uptick in mosquitoes in Mexico City from 2019, when we first lived there, to today.

Nepal, nearly free of mosquito-borne diseases until recently, saw dengue cases explode from 135 in 2015 to 28,109 in 2022.

Even more alarming, an estimated 40,000 viruses lurk in the bodies of mammals, of which a quarter could infect humans. Climate scientist Colin Carlson estimates that coming decades will see about 300,000 first encounters between species that normally don’t interact, leading to roughly 15,000 spillovers of viruses into new hosts.

The pattern extends beyond mosquitoes. Lyme disease cases in the US have tripled since the late 1990s. It’s not just the heat expanding tick ranges, but also increasingly fragmented landscapes. As forests are carved into suburban developments, fox and owl populations decline, leading to explosions in white-footed mice populations—the main reservoir for Lyme disease. Young ticks feed on infected mice, then spread the disease to humans.

We’re not just heating the planet—we’re creating a massive biological experiment with unpredictable results.

Antarctica: The Doomsday Glacier and Our Coastal Future

Of all the places on Earth, Antarctica might seem the least connected to our daily lives. Yet what happens to the ice sheets there will determine the future of every coastal city on the planet.

Goodell takes us on a research expedition to Thwaites Glacier—nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier”—one of the largest glaciers in West Antarctica. The question driving their research is stark: Is the West Antarctic ice sheet on the verge of unstoppable collapse?

A stable ice sheet means coastal cities have time to adapt. An unstable ice sheet means goodbye to Miami, New York, Shanghai, Mumbai—virtually every low-lying coastal city in the world, including our hometown of Long Beach, California.

To understand the risk, consider this: Seventy percent of Earth’s water is frozen in Antarctica’s ice sheets, some nearly three miles thick. If all of Greenland melted, sea levels would rise 22 feet. If Antarctica melted? Two hundred feet. The world’s coastlines would be obliterated.

Three million years ago, when atmospheric CO2 levels were similar to today and temperatures only slightly warmer, sea levels were at least 20 feet higher. This suggests massive melting is already “baked in” to our future. The only question is how fast it happens.

The mechanism of potential catastrophe is elegant in its terrifying simplicity. Large parts of West Antarctica’s glaciers lie below sea level, resting on ground that slopes downward inland—imagine a giant soup bowl filled with ice. Warm ocean water can penetrate under the ice, melting it from below. As the glacier retreats down the slope, more ice is exposed to warm water, accelerating the melt in a feedback loop that scientists call “marine ice sheet instability.”

The False Promise of Technological Salvation

As someone who advocates for using technology to augment human capabilities, I was particularly struck by Goodell’s analysis of air conditioning—our primary technological response to heat.

Here’s the uncomfortable reality: Air conditioning is not a cooling technology at all. It’s simply a tool for heat redistribution, moving thermal energy from inside to outside while consuming massive amounts of electricity.

The global spread of AC is accelerating climate change even as it provides temporary relief. In China, 75 percent of homes in Beijing and Shanghai now have air conditioning, up from near zero twenty years ago. Over the last decade, 10 percent of China’s skyrocketing electricity growth has been due to cooling—in a country still largely dependent on coal.

As one researcher put it: “Comfort is destroying the future, one click at a time.”

Pakistan produces about 0.5 percent of global CO2 emissions, and the average Pakistani is responsible for less than one-fifteenth the emissions of an American. Yet Pakistanis suffer disproportionately from extreme heat they didn’t create. When the power fails—as it often does—the consequences are deadly. In Sahiwal, eight babies died in a hospital ICU when extreme heat combined with a power outage shut down the air conditioning.

The Montreal Protocol, adopted in 1987, offers both a model of hope and a reason for caution. When scientists discovered that CFCs were destroying the ozone layer, the world acted swiftly. Within two years, an international treaty cut CFC use in half. Today, they’re outlawed by 197 countries, and the ozone layer is slowly recovering.

But we replaced CFCs with HFCs—chemicals that don’t harm ozone but are greenhouse gases up to 15,000 times more potent than CO2. Every solution can create new problems.

Heat as a Hyperlocal Phenomenon

One of Goodell’s most important insights is that heat waves are more like stories than meteorological events. Each has its own setting, cast of characters, and dramatic flash points.

A 99-degree day in Buffalo is fundamentally different from a 99-degree day in Las Vegas—not just meteorologically, but sociologically. Buffalo residents are less likely to have air conditioning, less experienced in dealing with extreme heat, and less connected to social networks that check on vulnerable neighbors.

The U.S. National Weather Service ranking system reflects this confusion. Heat watches, warnings, and advisories have no standardized definitions—local offices decide what each category means in their area.

Nobody should die in a heat wave. People die because they are alone, lack resources, don’t understand warning signs, or fear losing their jobs if they stop working. They die from ignorance about basic heat safety: whether to open windows, how much water to drink, when cold baths help or hurt, what a racing heart means.

The 2003 European heat wave killed 15,000 people in France in less than two weeks. Nearly a thousand lived in central Paris, many in top-floor apartments where heat built up beneath zinc roofs, literally cooking residents as if in an oven. It took weeks to recover all the bodies. Entire buildings had to be evacuated due to the pervasive smell of death.

Yet France now has one of the world’s best heat warning systems. Answers exist if we choose to implement them.

The Great Adaptation: Engineering for a Superheated World

Reading Goodell’s prescriptions for urban adaptation, I recognized parallels to the challenges we face in personal knowledge management and artificial intelligence. Just as we need to retrofit our thinking systems for information abundance, we need to retrofit our cities for thermal abundance.

The challenges are twofold:

First, how do we ensure new growth happens in heat-smart ways? Another fifty years of suburban sprawl would be catastrophic. Cities need density, public transit, green space, trees, water features, shade, and thermally intelligent design. Every new building should be both efficient and survivable during power outages.

Second, how do we fix what already exists? The vast majority of current buildings are ill-suited for extreme heat—poorly insulated, badly sited, dependent on air conditioning. Do we tear down and rebuild? Retrofit? How do we add green space to crowded cities? How do we banish concrete and invite nature?

Trees are climate heroes, but they’re also climate victims. In 2011, combined drought and heat killed 10 percent of urban trees in Texas—six million died in months. Analysis suggests that in a midrange warming scenario, three-quarters of urban trees could die from heat and drought by 2050. Globally, we’re losing ten billion trees annually while planting only five billion.

We need new approaches, new species, and new ways of thinking about urban ecosystems. It’s the greatest engineering challenge of our time.

From Information to Transformation

As I finished Goodell’s book, I kept returning to a fundamental question: Why do we struggle to act on information about slow-moving catastrophes?

The answer lies partly in how our brains process threats. We’re wired for immediate dangers, not gradual degradation. But it also reflects a failure of our systems for capturing, organizing, and acting on critical information.

Climate change is, I believe, fundamentally a knowledge management problem. We have the data. We understand the mechanisms. We even know many of the solutions. What we lack is the ability to transform information into action at the necessary scale and speed, and the motivation and consensus needed to do so.

This is where I think the principles of Building a Second Brain, especially when augmented by the latest AI models, could be useful. We can use such systems to:

- Capture the full scope of climate impacts across all domains of life

- Organize information in ways that reveal connections and dependencies

- Distill insights into achievable objectives, actionable plans to realize them, and targets for advocacy and funding

- Create solutions in forms that motivate change, and express them in language and stories that resonate with more people

The heat crisis demands that we extend the principles of individual productivity and business growth that have shaped the modern world to the realm of collective survival.

Goodell’s book ends with a preview of our transformed future: “The tree you used to climb when you were a kid will die. The beach where you kissed your partner will be underwater. Mosquitoes and other insects will be year-round companions. New diseases will emerge. Cults of cool will celebrate the spiritual purity of ice. You’ll grill slabs of lab-grown ‘meat’ and drink Zinfandel from Alaska. Your digital watch will monitor your internal body temperature. Border walls will be fortified. Entrepreneurs will make millions selling you micro cooling devices. Fourth of July celebrations will become life-threatening events. Snow will feel exotic.”

This isn’t dystopian fiction. It’s the trajectory we’re already on.

But trajectories can change. The Montreal Protocol proved we can act swiftly when we understand the threat. The question is whether we can process information about heat—diffuse, gradual, unequally distributed—with the same clarity that allowed us to recognize the ozone hole.

What You Can Do Now

Knowledge without action is merely fuel for anxiety. Here are concrete steps you can take to begin adapting to our heating world:

For Personal Safety:

- Learn the signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke—for yourself and loved ones

- Understand that hydration alone won’t prevent heat stroke; cooling is essential

- Create a heat emergency plan, including cooling strategies and communication with vulnerable neighbors

- Never take Tylenol or aspirin for heat-related symptoms

For Your Home and Work:

- Assess your spaces for passive cooling opportunities (shade, ventilation, insulation)

- Create backup plans for power outages during heat waves

- Consider heat resilience in any renovation or moving decisions

- Plant trees and create green spaces wherever possible

For Your Community:

- Advocate for heat action plans in your city

- Support urban greening initiatives

- Join or create networks that check on vulnerable neighbors during heat waves

- Push for workplace heat safety standards

For Systemic Change:

- Make climate action a non-negotiable criterion for your political choices

- Divest from fossil fuels and invest in climate-friendly industries

- Support organizations working on climate adaptation

- Share knowledge about heat risks and solutions in your networks

The coming heat will kill—but it doesn’t have to kill you or those you care about. With the right information, preparation, and collective action, we can adapt to the thermal transformation of our planet.

The challenge isn’t just surviving the heat. It’s maintaining our humanity, creativity, and capacity for joy in a world growing hotter by the day. That’s a project worthy of our best thinking, our most innovative technology, and our deepest commitment to each other.

The future may be hot, but it doesn’t have to be hopeless.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Life and Death on a Scorched Planet: What I Learned From “The Heat Will Kill You First” appeared first on Forte Labs.

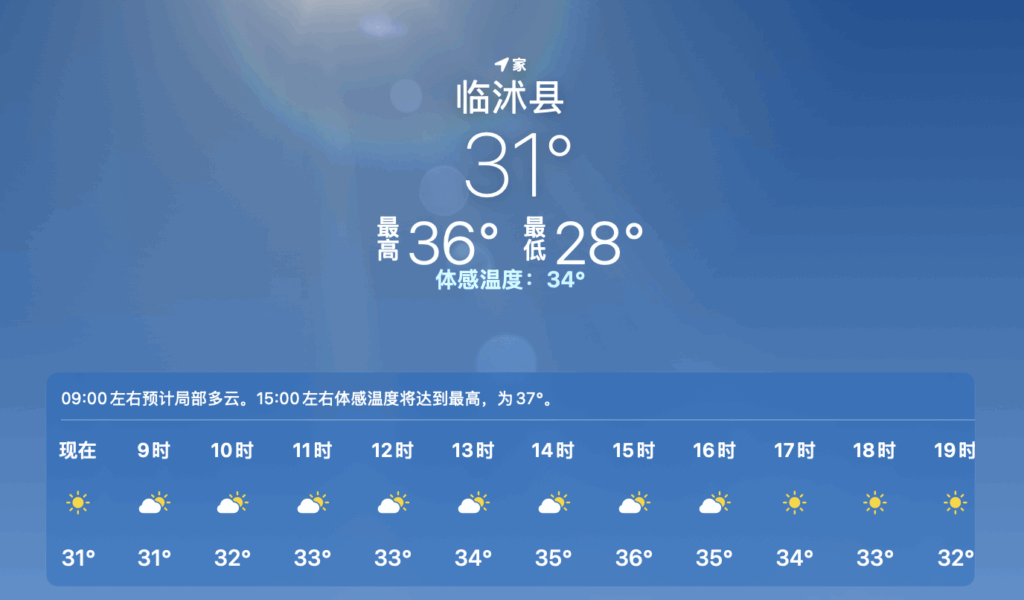

。如果天气能凉快一些,或许能好一些。

。如果天气能凉快一些,或许能好一些。